Some notes on the oldest watch brands – Jaquet Droz, 1738

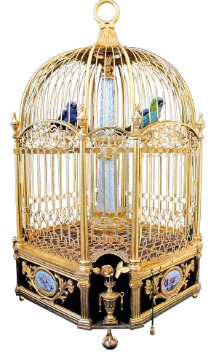

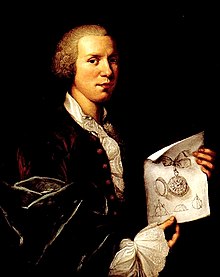

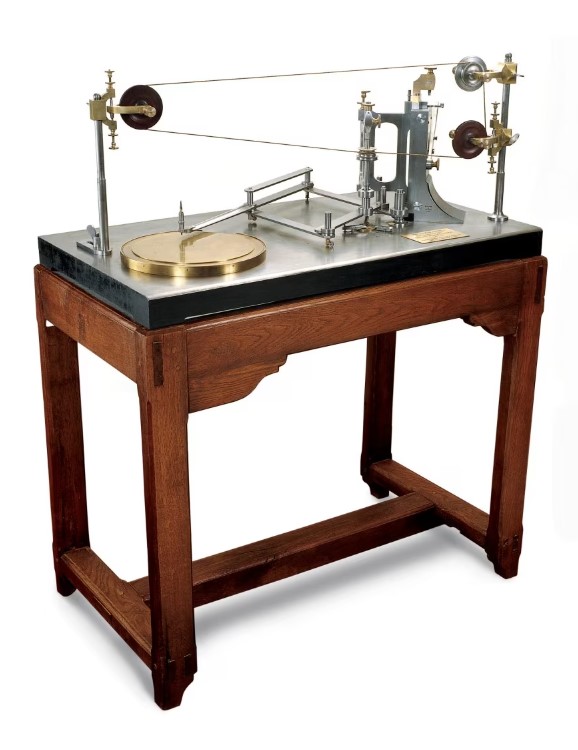

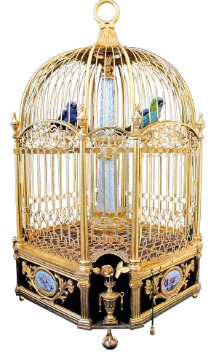

The remarkable story of Jaquet Droz is one that would have been worthy of being romanced by Alexandre Dumas. Pierre Jaquet-Droz (1721-1790) was famous for his automata – robot-like wind-up toys that performed human functions such as writing or pouring a cup of tea; others were in the shape of animals, including dogs that barked and birds that sang.

The craftsmanship involved in developing and building such complicated contraptions earned Jaquet Droz the accusation of sorcery, but his machines were so popular that he never faced real troubles.

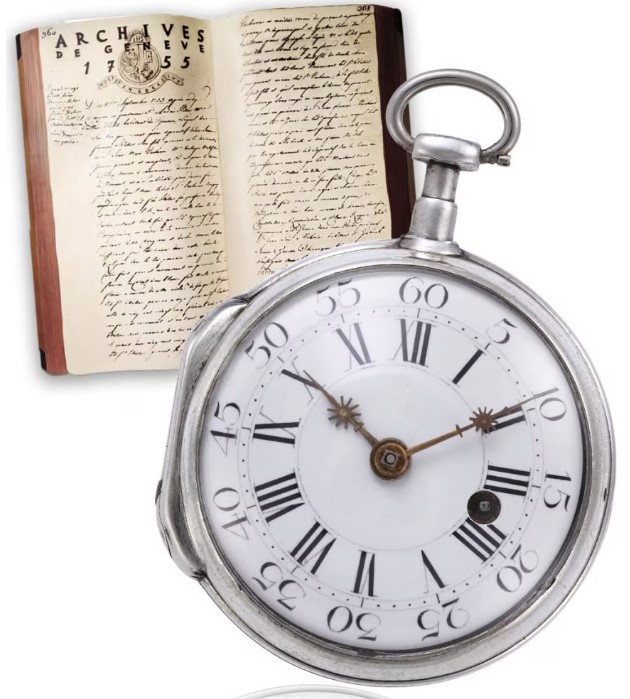

Jaquet Droz learned clockmaking at a young age eventually setting up workshop in 1738 and developing a deep interest for sophisticated movements which he developed and eventually enhanced with the addition of music and automata. His extravagant products soon attracted the attention of a wealthy clientèle, always on the lookout in that age for the new and bizarre with which to impress peers and higher nobility and possibly climb social hierarchies.

This is how, after an unlucky familiar history (lost the wife and a daughter early), he met George Keith, Earl Marischal, governor of the principality of Neuchâtel, who advised him to present his creations abroad, especially in Spain where he could help introduce him to the court. Jaquet Droz didn’t hesitate to take the invitation, loaded a cart full of automata and went to Madrid. As things worked with absolute sovereigns of that time, after the 7 week trip he had to wait for several months before actually being able to present his work to the royal court. But the wait paid off, King Ferdinand VI of Spain was blown away by the machines, so much so that he bought all of them for a sum that in today’s money could have been something around 1M$.

With the influx of money Jaquet Droz was able to invest even more in automata and complicated clockworks which he perfected and marketed slowly acquiring international notoriety. He visited the courts of France (yes, Louis XIV and Marie Antoinette just 18 years before they lost their heads), Flanders, Russia, England, where he decided to set up a workshop. London gave him the opportunity to expand worldwide, going as far as China, where he was represented by the famous James Cox trading company, and becoming the first clockmaking brand to be imported there. Jaquet Droz original pieces are still preserved in the Imperial Palace Museum today.

Long story short, Jaquet Droz became a successful international brand with three production and profit centers: one in La Chaux-de-Fonds, a second in London as well as a third in Geneva dedicated to low-volume watchmaking production. Sales were handled by agents in France for the most part, but also in London and Canton. 1788 was the peak of JD’s success. But, being his success was exclusively dependent on his customers, and being his customers part of the establishment of the times, it all started falling apart with the French revolution. Suddenly the big-shot clients disappeared or were unable to pay their orders. In addition, misfortune again struck JD’s personal life, he died in 1790 and his son the following year. JD’s remaining associate and adoptive son, Jean-Frédéric Leschot, ran into serious financial difficulties. He continued to make high-priced watches, snuffboxes and singing birds, but had to show great prudence: customers were notified that he now preferred to be paid cash on delivery and would no longer sell to faraway markets. The Napoleonic Wars, which pitted France against nearly every other nation of Europe, put an end to prosperity for the nobility and well-to-do bourgeoisie. The Continental Blockade, decreed by Napoleon in 1806, killed off any remaining market for very luxurious objects and greatly inhibited trade with England. For Jaquet-Droz & Leschot, this was the end of a period of great creativity and prosperity.

Leschot continued watchmaking as did his offspring, but the brand Jaquet Droz was forgotten and sources are inconclusive.

A Jaquet Droz SA existed in the 20th centuries producing unspectacular watches but this also disappeared in 1963.

The Jaquet-Droz name was revived as a shared brand by the Coopérative de Fabricants Suisses d'Horlogerie (FH) in 1965. For nearly 20 years, a wide range of “Jaquet-Droz” branded watches were distributed and sold worldwide but produced by “150 manufacturers.” It was later incorporated as SAH. This concern also finally failed in 1983.

It was resurrected in 1995 by two former Breguet employees who bought the rights of the name and assembled and sold (get that) replicas of the original JD automata. They also produced “upscale” watches with modest success. Again in financial dire straits, eventually the Swatch Group purchased the brand and relaunched it as a small-production, high-grade watch company that uses updated and modified movements based on Frédéric Piguet calibers (also part of the Swatch Group via Blancpain).

JD’s signature watches today are the Grande Seconde, featuring two overlapping dials set into the main dial; models thereof range today from extremely modern versions with bright white enamel dials and minimal markings to more baroque versions featuring precious stoines´, colourful enamel work and hand engraving.

JD also crafts miniaturized automata that are just as striking today as they were 300 years ago.

The remarkable story of Jaquet Droz is one that would have been worthy of being romanced by Alexandre Dumas. Pierre Jaquet-Droz (1721-1790) was famous for his automata – robot-like wind-up toys that performed human functions such as writing or pouring a cup of tea; others were in the shape of animals, including dogs that barked and birds that sang.

The craftsmanship involved in developing and building such complicated contraptions earned Jaquet Droz the accusation of sorcery, but his machines were so popular that he never faced real troubles.

Jaquet Droz learned clockmaking at a young age eventually setting up workshop in 1738 and developing a deep interest for sophisticated movements which he developed and eventually enhanced with the addition of music and automata. His extravagant products soon attracted the attention of a wealthy clientèle, always on the lookout in that age for the new and bizarre with which to impress peers and higher nobility and possibly climb social hierarchies.

This is how, after an unlucky familiar history (lost the wife and a daughter early), he met George Keith, Earl Marischal, governor of the principality of Neuchâtel, who advised him to present his creations abroad, especially in Spain where he could help introduce him to the court. Jaquet Droz didn’t hesitate to take the invitation, loaded a cart full of automata and went to Madrid. As things worked with absolute sovereigns of that time, after the 7 week trip he had to wait for several months before actually being able to present his work to the royal court. But the wait paid off, King Ferdinand VI of Spain was blown away by the machines, so much so that he bought all of them for a sum that in today’s money could have been something around 1M$.

With the influx of money Jaquet Droz was able to invest even more in automata and complicated clockworks which he perfected and marketed slowly acquiring international notoriety. He visited the courts of France (yes, Louis XIV and Marie Antoinette just 18 years before they lost their heads), Flanders, Russia, England, where he decided to set up a workshop. London gave him the opportunity to expand worldwide, going as far as China, where he was represented by the famous James Cox trading company, and becoming the first clockmaking brand to be imported there. Jaquet Droz original pieces are still preserved in the Imperial Palace Museum today.

Long story short, Jaquet Droz became a successful international brand with three production and profit centers: one in La Chaux-de-Fonds, a second in London as well as a third in Geneva dedicated to low-volume watchmaking production. Sales were handled by agents in France for the most part, but also in London and Canton. 1788 was the peak of JD’s success. But, being his success was exclusively dependent on his customers, and being his customers part of the establishment of the times, it all started falling apart with the French revolution. Suddenly the big-shot clients disappeared or were unable to pay their orders. In addition, misfortune again struck JD’s personal life, he died in 1790 and his son the following year. JD’s remaining associate and adoptive son, Jean-Frédéric Leschot, ran into serious financial difficulties. He continued to make high-priced watches, snuffboxes and singing birds, but had to show great prudence: customers were notified that he now preferred to be paid cash on delivery and would no longer sell to faraway markets. The Napoleonic Wars, which pitted France against nearly every other nation of Europe, put an end to prosperity for the nobility and well-to-do bourgeoisie. The Continental Blockade, decreed by Napoleon in 1806, killed off any remaining market for very luxurious objects and greatly inhibited trade with England. For Jaquet-Droz & Leschot, this was the end of a period of great creativity and prosperity.

Leschot continued watchmaking as did his offspring, but the brand Jaquet Droz was forgotten and sources are inconclusive.

A Jaquet Droz SA existed in the 20th centuries producing unspectacular watches but this also disappeared in 1963.

The Jaquet-Droz name was revived as a shared brand by the Coopérative de Fabricants Suisses d'Horlogerie (FH) in 1965. For nearly 20 years, a wide range of “Jaquet-Droz” branded watches were distributed and sold worldwide but produced by “150 manufacturers.” It was later incorporated as SAH. This concern also finally failed in 1983.

It was resurrected in 1995 by two former Breguet employees who bought the rights of the name and assembled and sold (get that) replicas of the original JD automata. They also produced “upscale” watches with modest success. Again in financial dire straits, eventually the Swatch Group purchased the brand and relaunched it as a small-production, high-grade watch company that uses updated and modified movements based on Frédéric Piguet calibers (also part of the Swatch Group via Blancpain).

JD’s signature watches today are the Grande Seconde, featuring two overlapping dials set into the main dial; models thereof range today from extremely modern versions with bright white enamel dials and minimal markings to more baroque versions featuring precious stoines´, colourful enamel work and hand engraving.

JD also crafts miniaturized automata that are just as striking today as they were 300 years ago.