This thread is me simply sharing what I learn from a little resarch on the internet about horology history and watch brands. Was always interested in history and I like to discover the background of people, events, objects. Since I also like to be systematic, I'll tackle watch brands in chronological order, and I'll share my findings when I have the time to do the research. Don't get excited, most posts are the result of a couple of hours of research on the internet, anybody could do it. In this regards also a caveat: it's the internet, as much as I try to filter and collect the information critically, the sources are unconfirmed and often there's contradictory information. Hope you enjoy.

Some notes on the alleged Swiss supremacy in horology history

Disclaimer: this is the result of a couple of hours research in the net, for personal interest, which I'm just sharing. This time didn't warrant for source verification or 100% exactitude, so apologies if some information may be inaccurate.

A lot of people think that Swiss horology holds the first place in the business because of a long tradition being at the lead of horological evolution. But this isn’t true, the Swiss gained the leadership through a number of historical and social events in a long process that lasted some centuries.

First mechanical clocks appeared as early as the 13th century as weight-driven devices to regulate the timing of bells in churchtowers, the only time-telling method for most people at the time. Admittedly, the works involved were quite rudimentary and not entirely comparable to the mechanics of modern watches. But not much later, the mechanical principles underlying modern timekeeping devices started to evolve, and more advanced mechanical watches appeared more or less simultaneously in England, France and Italy, the most culturally advanced nations of the time. No Switzerland so far.

Peter Henlein from Nuremberg is generally regarded as the first modern watchmaker. A locksmith by trade he had the “opportunity” to learn watchmaking in a cloister where he sought protection from a murder charge, and between 1509 and 1530 he produced miniaturized clocks that could be worn as pendants. Still, these were too big to be carried in a pocket.

It is around this time that Huguenots (protestants) fleeing religious persecution from France began establishing themselves in Switzerland. Among those, several watchmakers that set up shop in Geneva. As a fortunate coincidence (for the watchmaking industry) at the same time, Protestant reformer John Calvin prohibited wearing jewelry. Therefore, Swiss jewelers got together with the foreign watchmakers and shifted their craft to producing timepieces, which were still not regarded as jewelry. Win-win. Curiously, the first registered “orologier” in Geneva was Frenchman Thomas Bayard in 1554. Also French Pierre Huaud and Jean Toutin, who brought the craftsmanship of enamel to Geneva. No Swiss yet…

Still, the most renowned watch craftsmanship was to be found around the royal courts of the renaissance or in those technological hubs that at the time coincided with big trading centers. It’s in these places that the rich and famous (royal families, nobility and merchants) had the possibility to spend real fortunes on timekeeping devices.

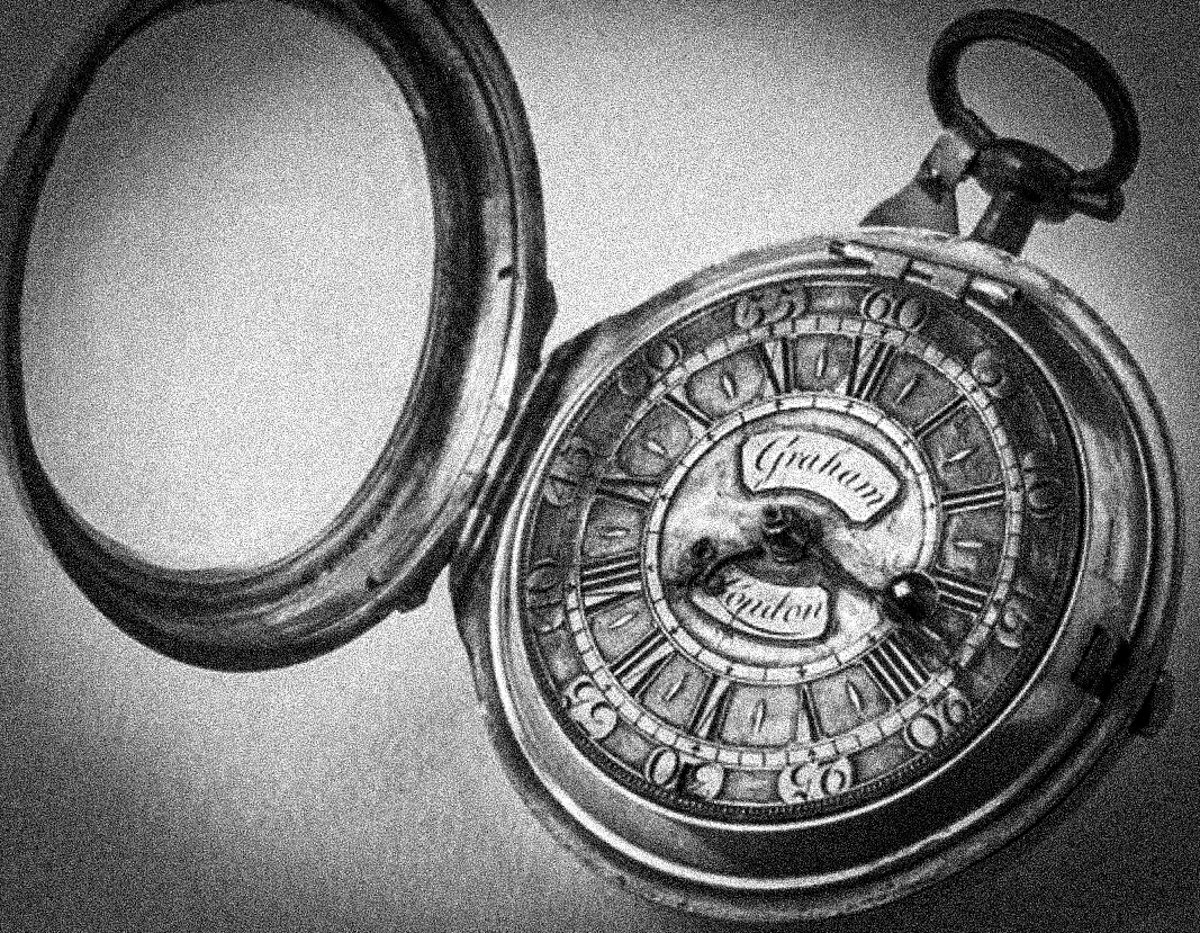

One of the first significant breakthroughs in watchmaking was the invention of the pendulum clock by Dutch horologist Christiaan Huygens in the mid 17th century. Inspired by Galileo Galilei’s research on oscillators, it was a weight-driven clock with a crown wheel (verge) escapement that increased the accuracy of clocks from about 15 minutes per day to 15 seconds per day. Later, the anchor escapement further improved accuracy. This is the Netherlands, not Switzerland.

The 18th century saw a lot of improvements mainly fostered by British watchmakers. The invention of the marine chronometer, the minute repeater, the lever escapement all originated in England. Meanwhile though, the Swiss horology industry was growing favored by the local social and economic conditions. Farmers had nothing to do in the harsh winters in the mountains, so they occupied themselves assembling components for Geneva-based watchmakers. The Swiss introduced principles of mass-production into horology: different parts would be manufactured in different places and then assembled by the manufacturers to create the final watches. This system gave Switzerland an enormous edge against its competitors in France, England and Germany. By the end of the 18th century, Geneva was able to export over 60.000 watches. Other countries were unable to compete with these volumes and the prices of mass-produced Swiss watches. Despite this, it is worth noting that the notable invention which allowed the Swiss industry to boom was actually developed in by a French watchmaker. In the 1760s Jean-Antoine Lépine, watchmaker to Louis XV, Louis XVI and Napoleon Bonaparte, invented the Lépine calibre – a simplified flat calibre that heralded the development of smaller pocket watches.

The 19th century finally saw the rise of the big traditional Swiss brands that still dominate the world of luxury watches today, but beware, they're not the oldest brands as well. Even if the Swiss watch industry may not have been at the head of horological evolution in its infancy years, it's undisputable that Swiss watchmaking, thanks to its importance and financial means gained by economic supremacy, set its lasting footprint on the advances in watchmaking in the last 2 centuries. I think Rolex, albeit the youngest of the traditional Swiss brands, embodies perfectly the role of Switzerland within horology history. Cunning marketing, exploitation of the market's conditions, genial design interspersed here and there with some great features we all love in our watches today.

Some notes on the alleged Swiss supremacy in horology history

Disclaimer: this is the result of a couple of hours research in the net, for personal interest, which I'm just sharing. This time didn't warrant for source verification or 100% exactitude, so apologies if some information may be inaccurate.

A lot of people think that Swiss horology holds the first place in the business because of a long tradition being at the lead of horological evolution. But this isn’t true, the Swiss gained the leadership through a number of historical and social events in a long process that lasted some centuries.

First mechanical clocks appeared as early as the 13th century as weight-driven devices to regulate the timing of bells in churchtowers, the only time-telling method for most people at the time. Admittedly, the works involved were quite rudimentary and not entirely comparable to the mechanics of modern watches. But not much later, the mechanical principles underlying modern timekeeping devices started to evolve, and more advanced mechanical watches appeared more or less simultaneously in England, France and Italy, the most culturally advanced nations of the time. No Switzerland so far.

Peter Henlein from Nuremberg is generally regarded as the first modern watchmaker. A locksmith by trade he had the “opportunity” to learn watchmaking in a cloister where he sought protection from a murder charge, and between 1509 and 1530 he produced miniaturized clocks that could be worn as pendants. Still, these were too big to be carried in a pocket.

It is around this time that Huguenots (protestants) fleeing religious persecution from France began establishing themselves in Switzerland. Among those, several watchmakers that set up shop in Geneva. As a fortunate coincidence (for the watchmaking industry) at the same time, Protestant reformer John Calvin prohibited wearing jewelry. Therefore, Swiss jewelers got together with the foreign watchmakers and shifted their craft to producing timepieces, which were still not regarded as jewelry. Win-win. Curiously, the first registered “orologier” in Geneva was Frenchman Thomas Bayard in 1554. Also French Pierre Huaud and Jean Toutin, who brought the craftsmanship of enamel to Geneva. No Swiss yet…

Still, the most renowned watch craftsmanship was to be found around the royal courts of the renaissance or in those technological hubs that at the time coincided with big trading centers. It’s in these places that the rich and famous (royal families, nobility and merchants) had the possibility to spend real fortunes on timekeeping devices.

One of the first significant breakthroughs in watchmaking was the invention of the pendulum clock by Dutch horologist Christiaan Huygens in the mid 17th century. Inspired by Galileo Galilei’s research on oscillators, it was a weight-driven clock with a crown wheel (verge) escapement that increased the accuracy of clocks from about 15 minutes per day to 15 seconds per day. Later, the anchor escapement further improved accuracy. This is the Netherlands, not Switzerland.

The 18th century saw a lot of improvements mainly fostered by British watchmakers. The invention of the marine chronometer, the minute repeater, the lever escapement all originated in England. Meanwhile though, the Swiss horology industry was growing favored by the local social and economic conditions. Farmers had nothing to do in the harsh winters in the mountains, so they occupied themselves assembling components for Geneva-based watchmakers. The Swiss introduced principles of mass-production into horology: different parts would be manufactured in different places and then assembled by the manufacturers to create the final watches. This system gave Switzerland an enormous edge against its competitors in France, England and Germany. By the end of the 18th century, Geneva was able to export over 60.000 watches. Other countries were unable to compete with these volumes and the prices of mass-produced Swiss watches. Despite this, it is worth noting that the notable invention which allowed the Swiss industry to boom was actually developed in by a French watchmaker. In the 1760s Jean-Antoine Lépine, watchmaker to Louis XV, Louis XVI and Napoleon Bonaparte, invented the Lépine calibre – a simplified flat calibre that heralded the development of smaller pocket watches.

The 19th century finally saw the rise of the big traditional Swiss brands that still dominate the world of luxury watches today, but beware, they're not the oldest brands as well. Even if the Swiss watch industry may not have been at the head of horological evolution in its infancy years, it's undisputable that Swiss watchmaking, thanks to its importance and financial means gained by economic supremacy, set its lasting footprint on the advances in watchmaking in the last 2 centuries. I think Rolex, albeit the youngest of the traditional Swiss brands, embodies perfectly the role of Switzerland within horology history. Cunning marketing, exploitation of the market's conditions, genial design interspersed here and there with some great features we all love in our watches today.

25.07.2023

Last edited: