“X-Ray Zulu 256 this is Golf Charlie Oscar Juliet, radio check, over.”

"GCOJ this is XZ256 reading you loud and clear, how me, over?"

"This is CCOJ loud and clear also. Please report position, over"

"This is XZ256, current position 35 nautical miles from mother, height 400ft. Weather is clear and dry, wind speed 10 knots bearing green 120, Visibility in excess of 10nm. Firing arcs are clear. Standing by to run".

“This is GCOJ Roger, confirmed firing arcs are clear. Stand by to execute, run when ready.”

“This is XZ256 Roger. Target acquired. Firing now, now, now.”

Sound familiar? A scene from Top Gun or any other Hollywood war movie? No, this is real life and one that sadly did not have a Hollywood ending.

On 12 June 2002, HMS ‘R’ (callsign GCOJ - aka mother) was conducting missile firing exercises with US friendly forces at the Virginia Cape Range off the coast of Norfolk, Virginia.

The exercise went well with successful Tomahawk cruise missile firings from HMS ‘R’ and Sea Skua missiles fired from her Lynx Mk8 helicopter (callsign XZ256). HMS ‘R’'s helicopter had a dual role during the exercise. As well as firing her Sea Skua missiles, she was also on station to video record the damage to the target.

Onboard XZ246 that day were 3 crew: the pilot, Lt RS, the flight observer, Lt JL and my brother, Petty Officer PH.

In the early hours of 13 June, back in the UK, some 3.500 miles away, I was sitting at my desk in the Royal Navy Police Headquarters, when the phone rang. Nothing unusual there. As police station watch commander, I was in charge of policing and investigation operations in an area covering Cheshire across to Yorkshire, all of Northern England, Scotland and Northern Ireland so calls came in from all over the command region at all times of the day and night.

What was unusual, was the beeping sound on the line indicating that the incoming call was coming from an Inmarsat satellite phone.

On the other end of the line was the senior police officer onboard HMS ‘R’, an old colleague of mine who was calling the RNPHQ as part of the Naval families next of kin casualty notification process. The news was not good.

Earlier that day, on completion of the exercise, Lynx XZ256 was returning to mother when the pilot made a Mayday transmission. Although most people may have heard this word many times in the movies (hopefully not in real life), it is important to highlight exactly what a 'Mayday’ call actually means. When the word ‘Mayday' is used in voice procedure radio communications, usually by aviators and sailors, it is used to signal that the ship or aircraft is experiencing a life-threatening emergency.

On hearing the Mayday call, HMS ‘R’s upper deck fire and emergency party commenced preparations for a COD (Crash on Deck) event. There was no need. Lynx XZ256 would never reach mother.

At a height of approximately 400ft, my brother heard a loud bang emanating from the starboard (right side) engine, immediately followed by a second bang. The aircraft had suffered a catastrophic double engine failure resulting in the aircraft experiencing an uncontrollable spin, nosediving into the water in excess of 120mph, where it quickly sank to a final depth of 4000m (13,000ft).

Sadly, Lt 'R' and Lt 'J' were killed on impact. Fortunately for my brother, the helicopter door was ripped off on impact creating an escape route and allowing him to swim free of the sinking aircraft. He was subsequently rescued some 15 mins later by a US Navy rescue helicopter scrambled from one of the US ships on the exercise.

My brother was lucky. He managed to escape due to still being in the floating harness he was using which allowed him to hang out of the aircraft whilst filming the missile shoot. Had he strapped himself in with his 6-point harness, he would have suffered a similar fate to that of his colleagues.

Strangely, my brother was not medivacked (medical evacuation of injured persons) to the US or the UK? Rather, he was kept onboard HMS ‘R’ for a WEEK for a ship's investigation, a very unusual decision especially when he was complaining of severe pain in his back and after the command being advised by both myself and the senior police officer onboard.

After being returned to the UK and given a weekend of rest (??) my brother was ordered to report to the Royal Naval Air Station Culdrose for an inquiry, and immediately thrown into an aircraft simulator where he re-lived those dreadful moments over and over again.

Having still not been sent for a medical examination by the navy he instead went to see a back specialist himself, some 5 weeks after the crash. The Doctor was quite disturbed that my brother had been walking around for 5 weeks. He had broken his back in 2 places as a result of the crash.

The Navy eventually raised XZ256 from its resting place some 2.5 miles down in the Hatteras Abyssal Plain. The deepest recovery of an aircraft in history at the time. They also recovered Lt ‘R's body. Lt ‘J’ was never found. I knew ‘J’, we served together on HMS ‘N’ a few years prior. She was a lovely person and to know she is still out there alone somewhere is incredibly sad.

Me and my brother never spoke about that day. We never spoke about anything to do with our service. Why would we? We were military, we were tough. We never spoke about the things we'd done, the things we'd seen. We didn't share our emotions publicly, or any other crap like that. If shit happened operationally or privately, you just put your big boy pants on, dried your eyes and 'cracked on'. No, we never spoke about that day.

At 1540, on Monday 26 June 2017, I was working from home when I received a call from my sister-in-law. She had found a suicide note from my brother saying he'd had enough of the years of suffering. I found him in the garage.

They call it survivor guilt, a form of PTSD. Apparently, he had been suffering all this time undiagnosed. We were tough, ex-military. We never spoke. Who knew?

In the funeral parlour I finally asked him about that day. There was of course no answer. He just lay there quietly and peacefully. We should have spoken.

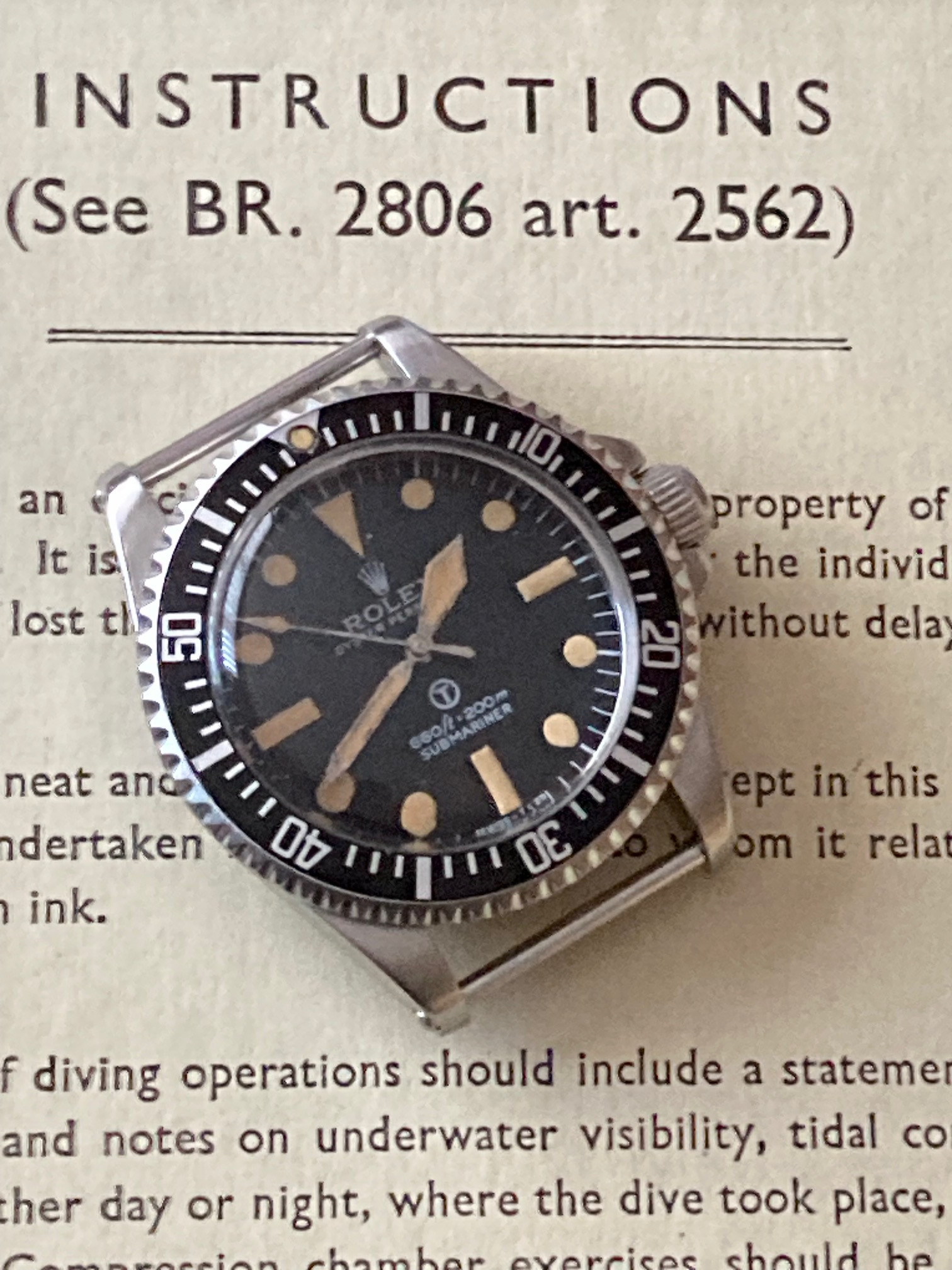

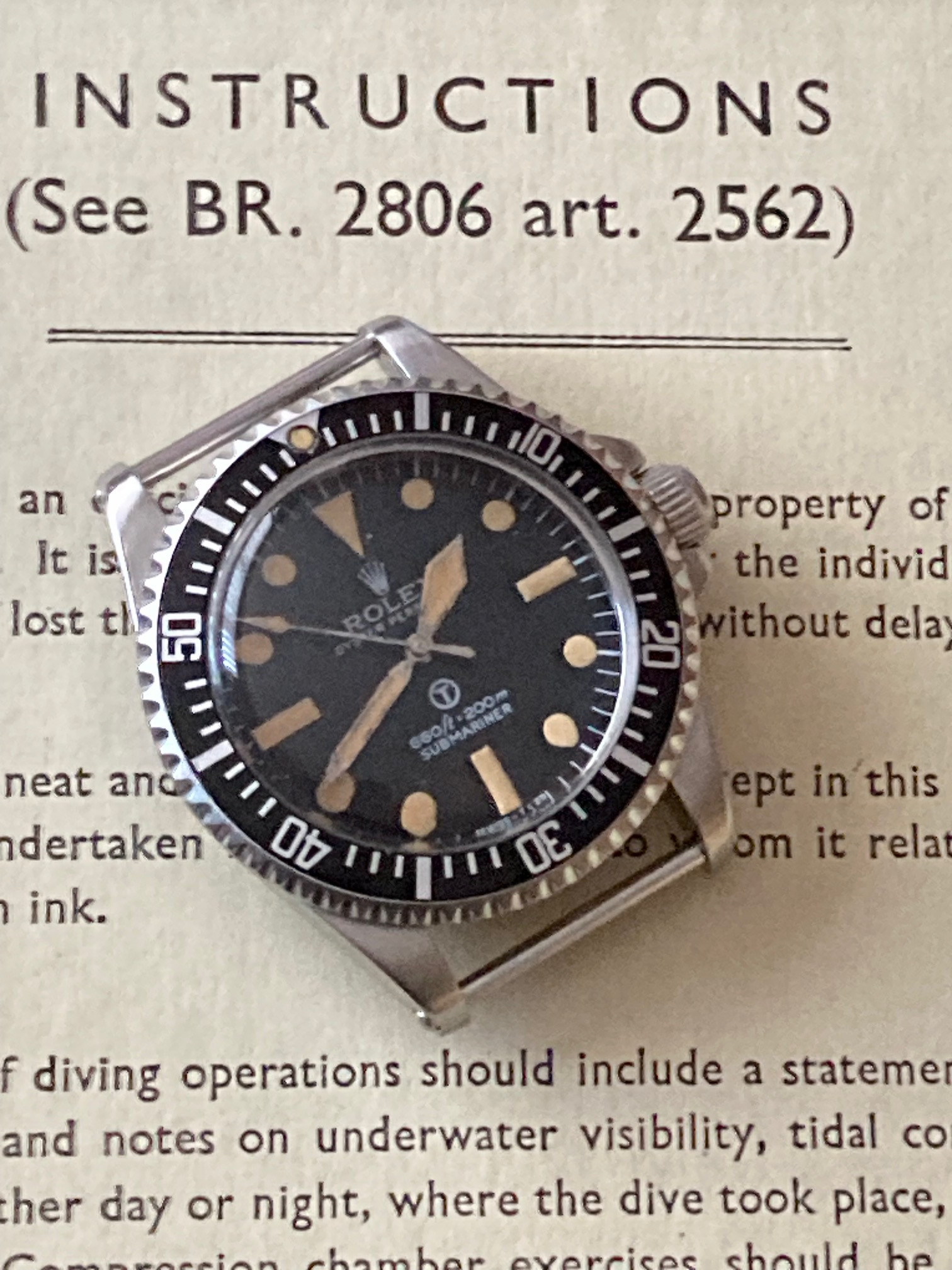

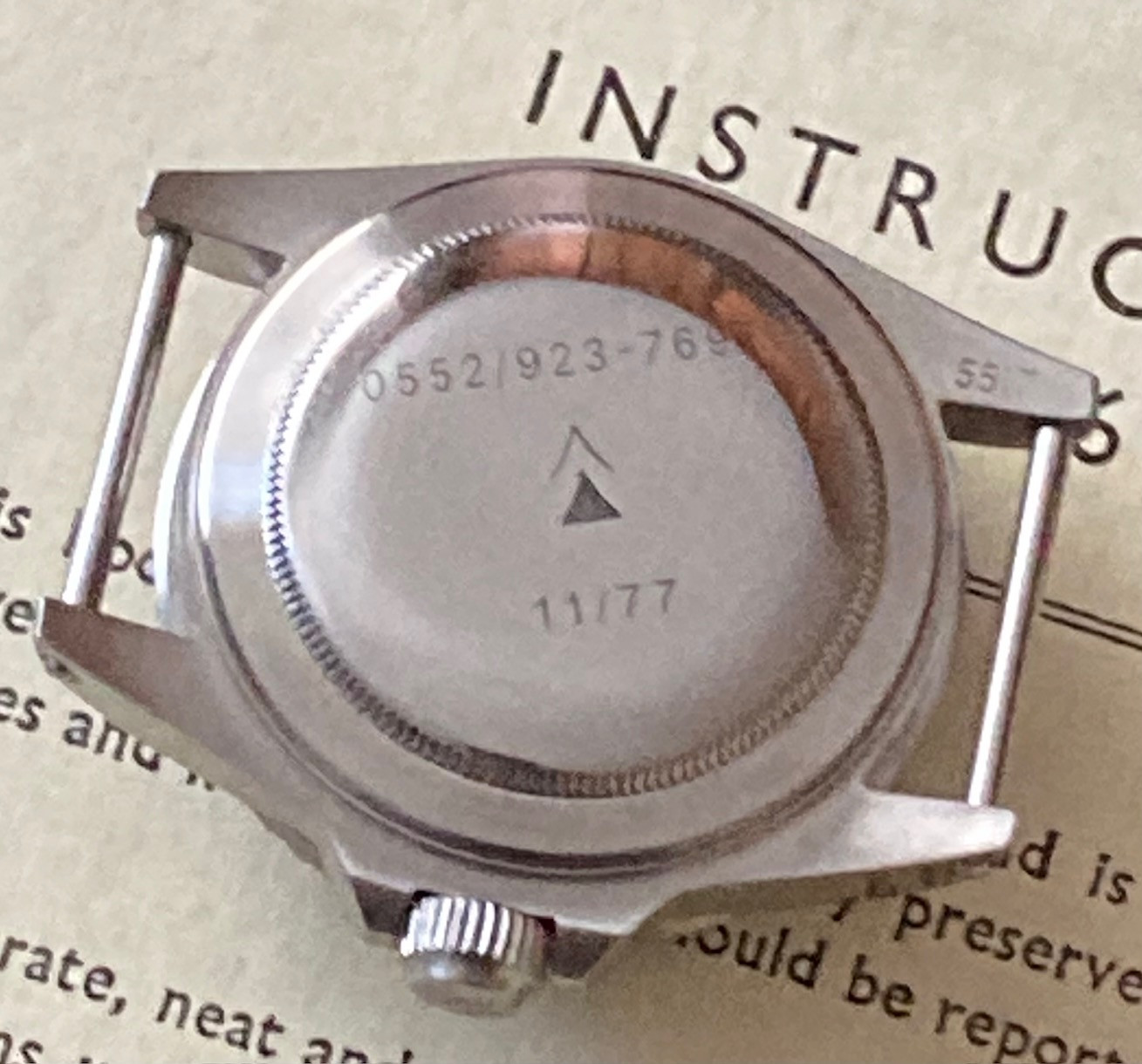

It had taken me years before I could finally talk about that day and when I saw the marvellous MilSub recreations by Natas78, I knew I had finally found something that would be a fitting homage to my brother's 24 years service.

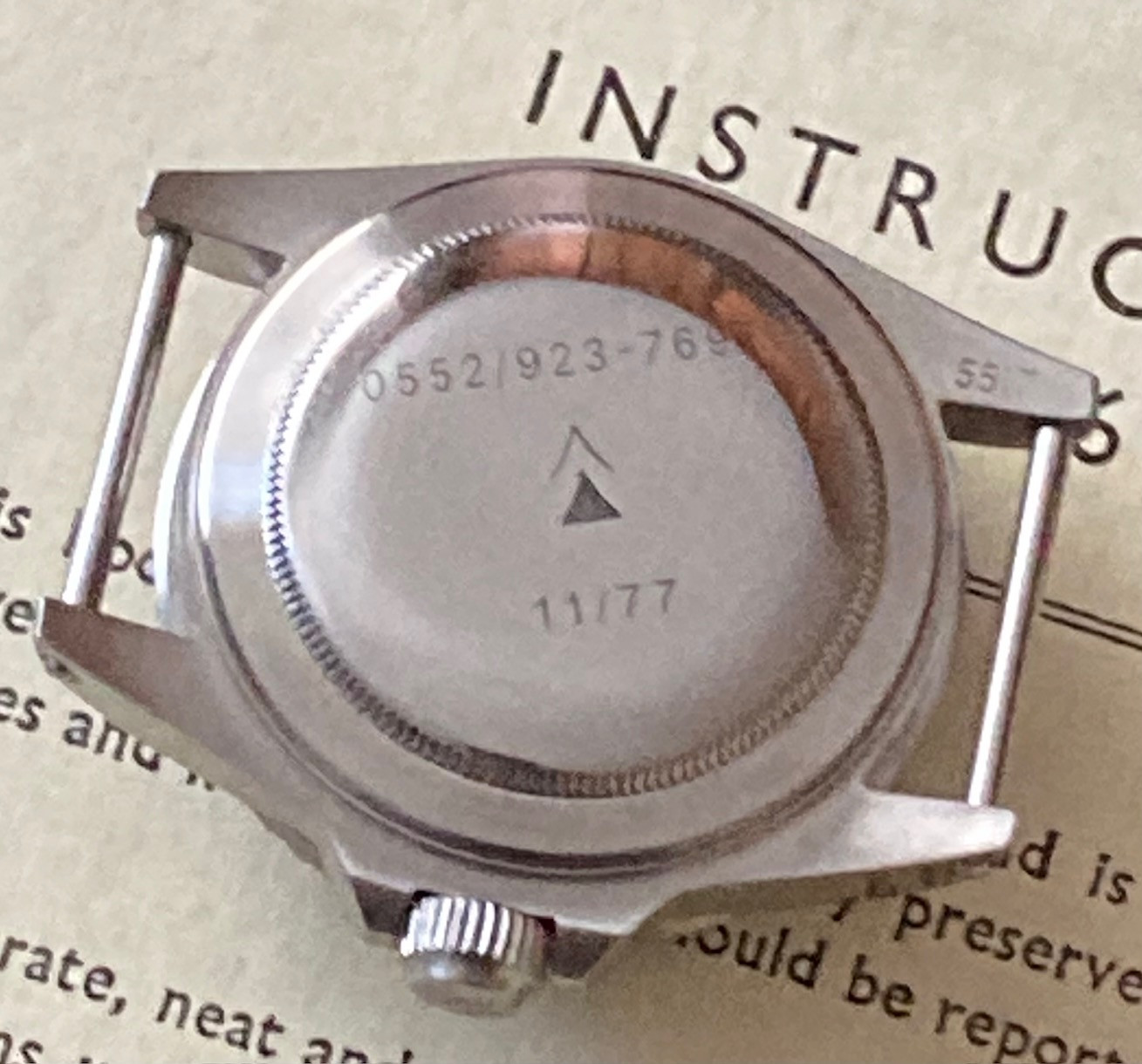

The workmanship really is superb. The watch serial number engraving was a special commission and is an amalgamation of mine and my brother’s service numbers. The reverse issue number and date was also commemorating a key date in my own service journey.

I only have a few pieces of my brother’s including his ships divers badge, divers nose clip and his presentation Sea Cadets knife he earned for seamanship back in 1978. His uniform and medals fittingly reside with his family.

I'm slowly getting better at talking about stuff. Not quite there yet but learning to open a little more. I guess what I'm trying to say is don't be like me and our kid. If shit happens don't just dry your eyes and crack on. Talk to someone.

Thanks Natas78, you have done us both proud.

"GCOJ this is XZ256 reading you loud and clear, how me, over?"

"This is CCOJ loud and clear also. Please report position, over"

"This is XZ256, current position 35 nautical miles from mother, height 400ft. Weather is clear and dry, wind speed 10 knots bearing green 120, Visibility in excess of 10nm. Firing arcs are clear. Standing by to run".

“This is GCOJ Roger, confirmed firing arcs are clear. Stand by to execute, run when ready.”

“This is XZ256 Roger. Target acquired. Firing now, now, now.”

Sound familiar? A scene from Top Gun or any other Hollywood war movie? No, this is real life and one that sadly did not have a Hollywood ending.

On 12 June 2002, HMS ‘R’ (callsign GCOJ - aka mother) was conducting missile firing exercises with US friendly forces at the Virginia Cape Range off the coast of Norfolk, Virginia.

The exercise went well with successful Tomahawk cruise missile firings from HMS ‘R’ and Sea Skua missiles fired from her Lynx Mk8 helicopter (callsign XZ256). HMS ‘R’'s helicopter had a dual role during the exercise. As well as firing her Sea Skua missiles, she was also on station to video record the damage to the target.

Onboard XZ246 that day were 3 crew: the pilot, Lt RS, the flight observer, Lt JL and my brother, Petty Officer PH.

In the early hours of 13 June, back in the UK, some 3.500 miles away, I was sitting at my desk in the Royal Navy Police Headquarters, when the phone rang. Nothing unusual there. As police station watch commander, I was in charge of policing and investigation operations in an area covering Cheshire across to Yorkshire, all of Northern England, Scotland and Northern Ireland so calls came in from all over the command region at all times of the day and night.

What was unusual, was the beeping sound on the line indicating that the incoming call was coming from an Inmarsat satellite phone.

On the other end of the line was the senior police officer onboard HMS ‘R’, an old colleague of mine who was calling the RNPHQ as part of the Naval families next of kin casualty notification process. The news was not good.

Earlier that day, on completion of the exercise, Lynx XZ256 was returning to mother when the pilot made a Mayday transmission. Although most people may have heard this word many times in the movies (hopefully not in real life), it is important to highlight exactly what a 'Mayday’ call actually means. When the word ‘Mayday' is used in voice procedure radio communications, usually by aviators and sailors, it is used to signal that the ship or aircraft is experiencing a life-threatening emergency.

On hearing the Mayday call, HMS ‘R’s upper deck fire and emergency party commenced preparations for a COD (Crash on Deck) event. There was no need. Lynx XZ256 would never reach mother.

At a height of approximately 400ft, my brother heard a loud bang emanating from the starboard (right side) engine, immediately followed by a second bang. The aircraft had suffered a catastrophic double engine failure resulting in the aircraft experiencing an uncontrollable spin, nosediving into the water in excess of 120mph, where it quickly sank to a final depth of 4000m (13,000ft).

Sadly, Lt 'R' and Lt 'J' were killed on impact. Fortunately for my brother, the helicopter door was ripped off on impact creating an escape route and allowing him to swim free of the sinking aircraft. He was subsequently rescued some 15 mins later by a US Navy rescue helicopter scrambled from one of the US ships on the exercise.

My brother was lucky. He managed to escape due to still being in the floating harness he was using which allowed him to hang out of the aircraft whilst filming the missile shoot. Had he strapped himself in with his 6-point harness, he would have suffered a similar fate to that of his colleagues.

Strangely, my brother was not medivacked (medical evacuation of injured persons) to the US or the UK? Rather, he was kept onboard HMS ‘R’ for a WEEK for a ship's investigation, a very unusual decision especially when he was complaining of severe pain in his back and after the command being advised by both myself and the senior police officer onboard.

After being returned to the UK and given a weekend of rest (??) my brother was ordered to report to the Royal Naval Air Station Culdrose for an inquiry, and immediately thrown into an aircraft simulator where he re-lived those dreadful moments over and over again.

Having still not been sent for a medical examination by the navy he instead went to see a back specialist himself, some 5 weeks after the crash. The Doctor was quite disturbed that my brother had been walking around for 5 weeks. He had broken his back in 2 places as a result of the crash.

The Navy eventually raised XZ256 from its resting place some 2.5 miles down in the Hatteras Abyssal Plain. The deepest recovery of an aircraft in history at the time. They also recovered Lt ‘R's body. Lt ‘J’ was never found. I knew ‘J’, we served together on HMS ‘N’ a few years prior. She was a lovely person and to know she is still out there alone somewhere is incredibly sad.

Me and my brother never spoke about that day. We never spoke about anything to do with our service. Why would we? We were military, we were tough. We never spoke about the things we'd done, the things we'd seen. We didn't share our emotions publicly, or any other crap like that. If shit happened operationally or privately, you just put your big boy pants on, dried your eyes and 'cracked on'. No, we never spoke about that day.

At 1540, on Monday 26 June 2017, I was working from home when I received a call from my sister-in-law. She had found a suicide note from my brother saying he'd had enough of the years of suffering. I found him in the garage.

They call it survivor guilt, a form of PTSD. Apparently, he had been suffering all this time undiagnosed. We were tough, ex-military. We never spoke. Who knew?

In the funeral parlour I finally asked him about that day. There was of course no answer. He just lay there quietly and peacefully. We should have spoken.

It had taken me years before I could finally talk about that day and when I saw the marvellous MilSub recreations by Natas78, I knew I had finally found something that would be a fitting homage to my brother's 24 years service.

The workmanship really is superb. The watch serial number engraving was a special commission and is an amalgamation of mine and my brother’s service numbers. The reverse issue number and date was also commemorating a key date in my own service journey.

I only have a few pieces of my brother’s including his ships divers badge, divers nose clip and his presentation Sea Cadets knife he earned for seamanship back in 1978. His uniform and medals fittingly reside with his family.

I'm slowly getting better at talking about stuff. Not quite there yet but learning to open a little more. I guess what I'm trying to say is don't be like me and our kid. If shit happens don't just dry your eyes and crack on. Talk to someone.

Thanks Natas78, you have done us both proud.